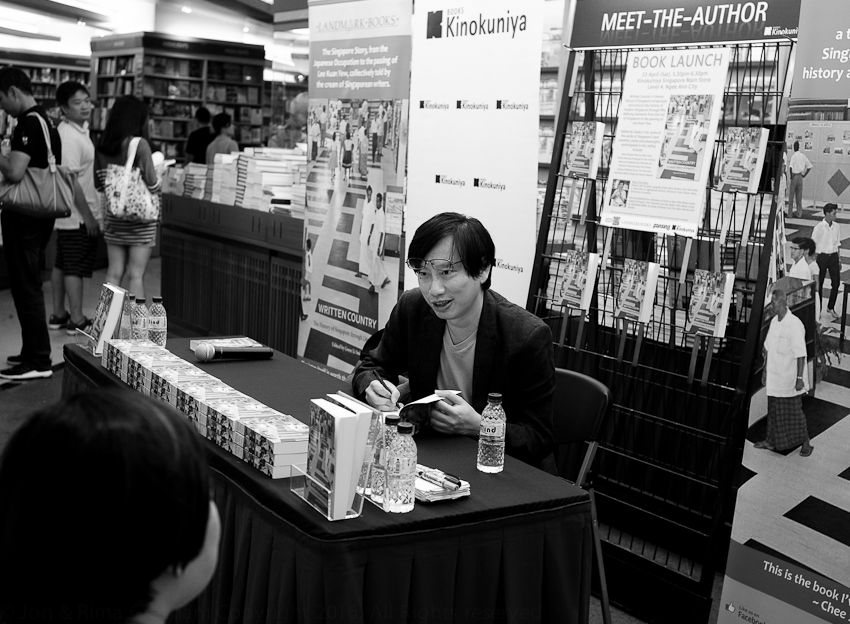

Written Country: The History of Singapore through Literature was launched at Kinokuniya last Saturday. The book is published by Landmark Books and edited by Gwee Li Sui.

This anthology tells Singapore’s history through excerpts of prose and poetry. A brief informative commentary on key events from the fall of Singapore to the death of Lee Kuan Yew accompanies the literary texts.

Gwee’s introduction sets out the editorial principles guiding his approach to the selection and arrangement of the texts. I like Gwee’s discussion of:

- the ’factually sound and the emotionally consistent’,

- the play between first hand and imagined experience,

- how history and literature relate to each other

What is the quality that literature possesses that makes history come alive and something more than a list of observed facts and descriptions?

In the very first text, Lim Thean Soo demonstrates this quality when he writes about the schoolboy who runs to the concrete roof of his family home to watch the shelling and counter shelling, and the bombs falling across Singapore on the 15th February 1942.

Gwee notes, inter alia, writers form characters that possess ’some quality of having lived through time’ and possessing deeper forms of knowledge by ‘allowing information to be thought back to us - accordingly rethought, made meaningful.’

Gwee writes ‘[a]s ... texts enter specific moments, they effectively give back to events their emotions and, in this way, generate reflections and commentaries from within.’

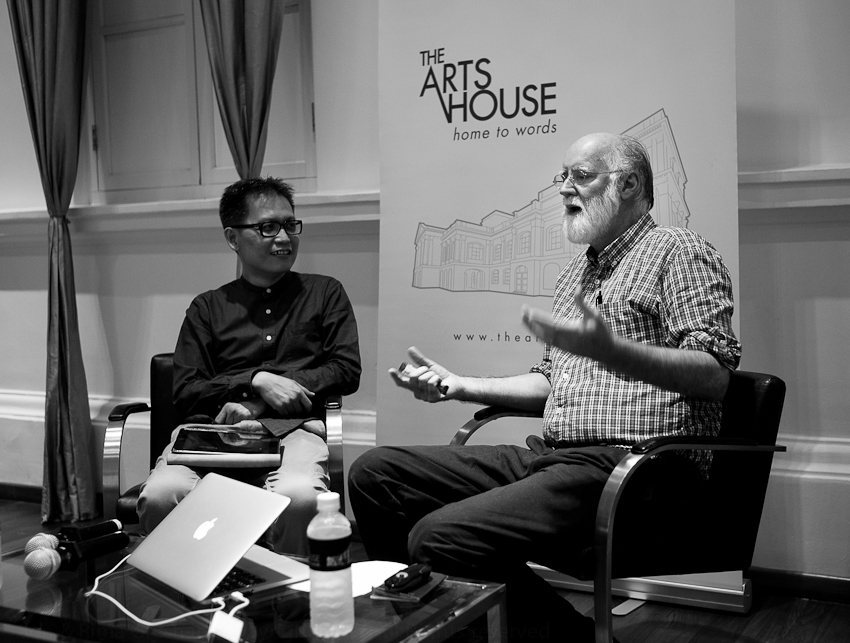

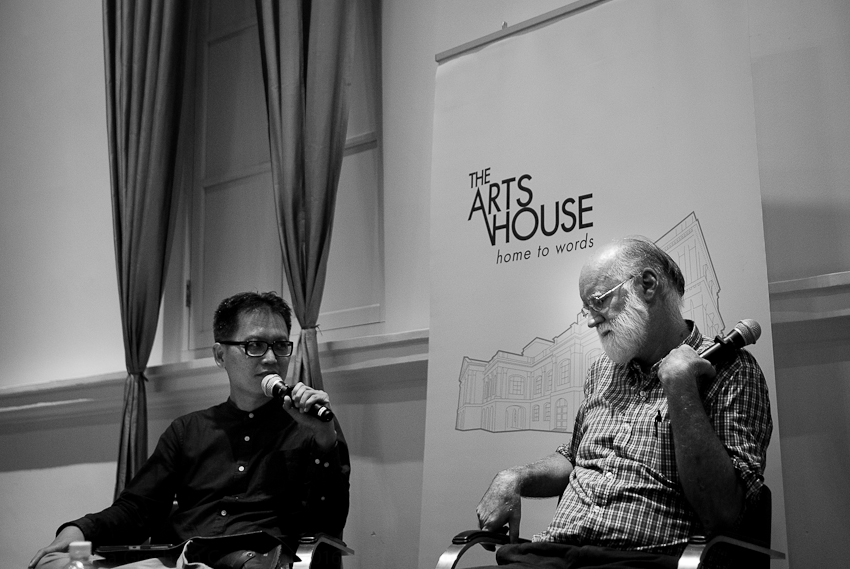

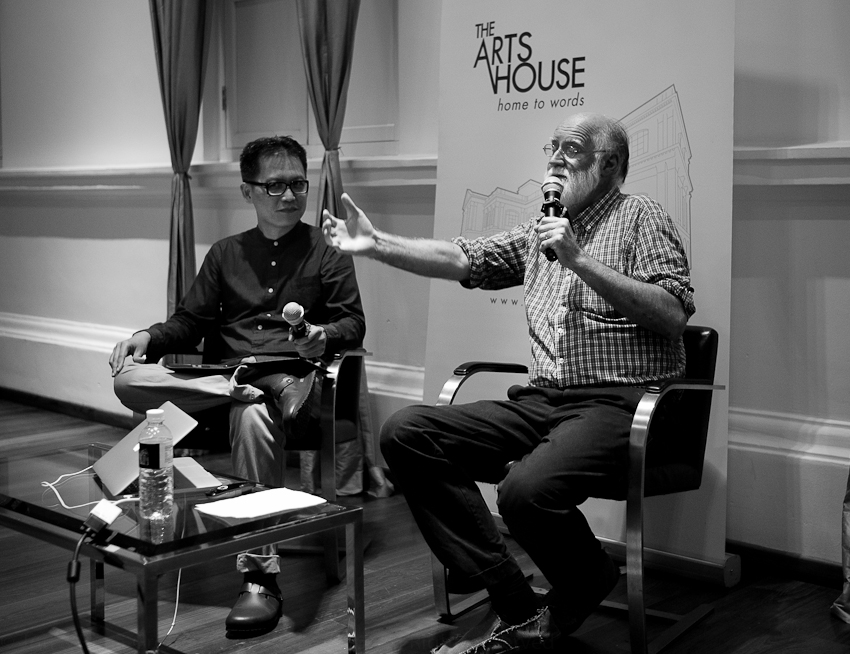

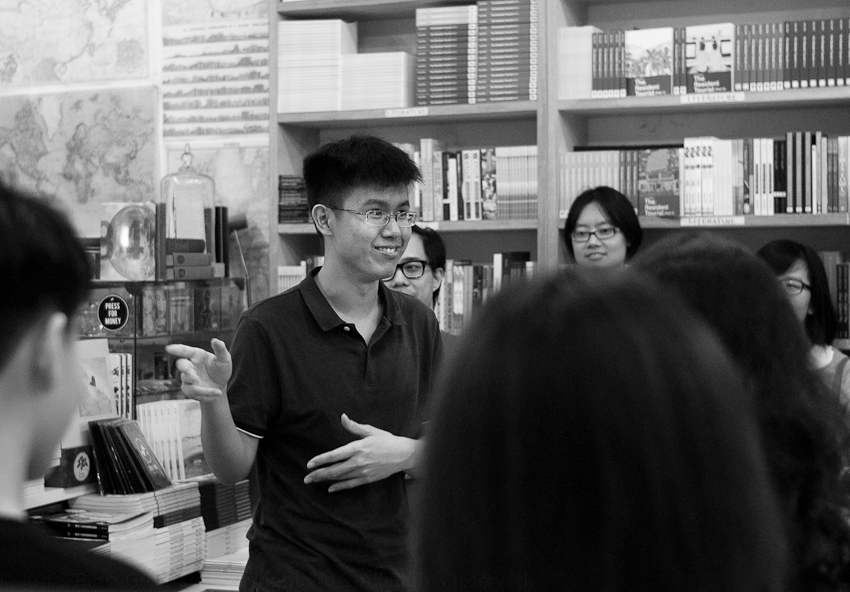

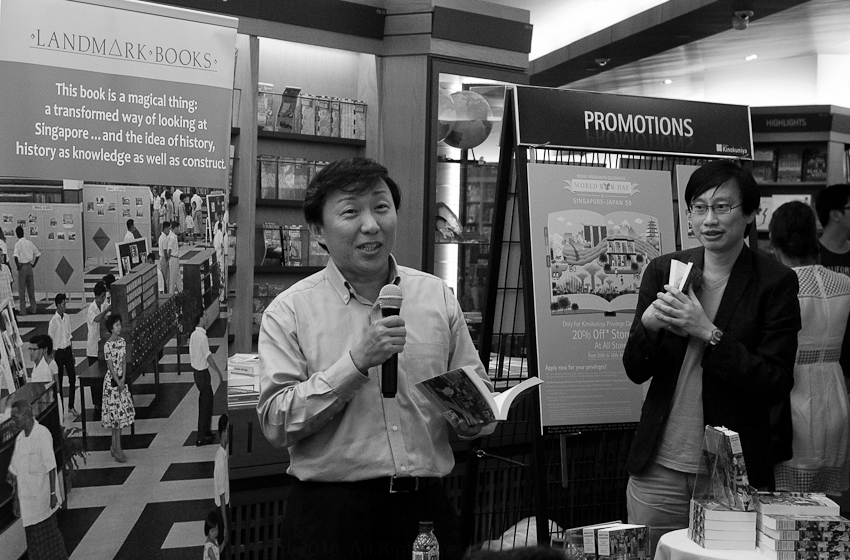

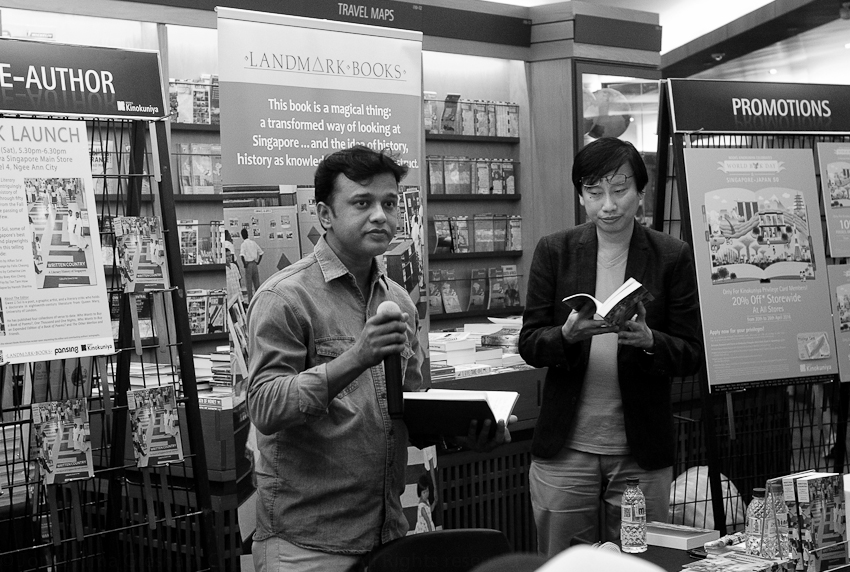

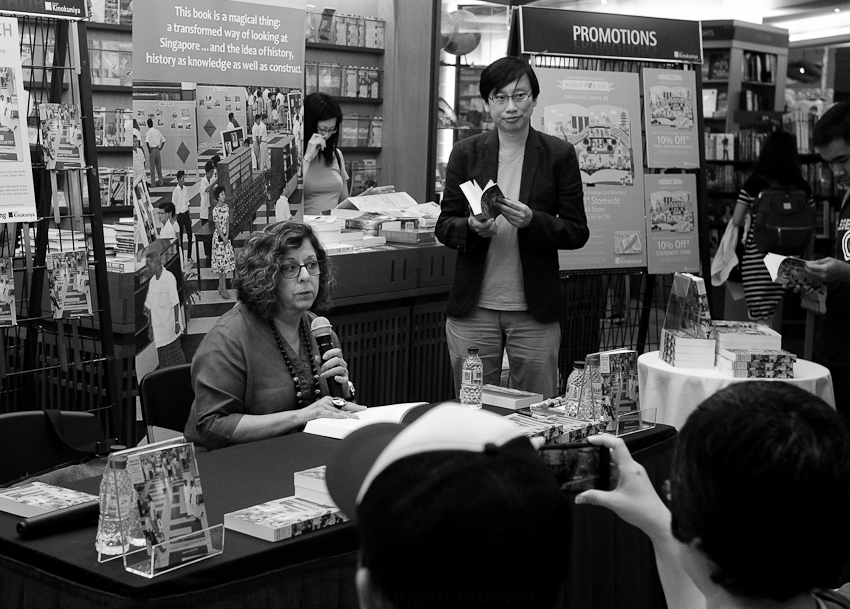

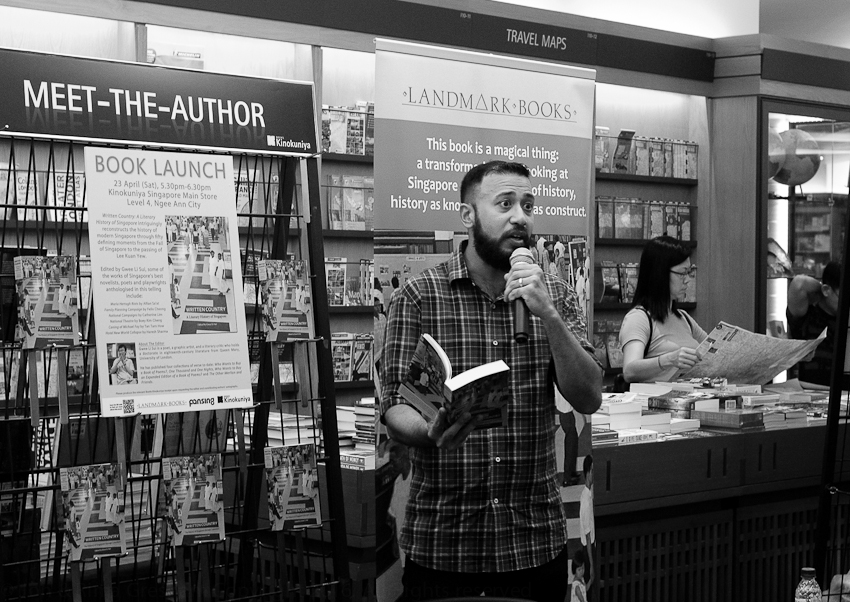

At the Kino launch:

- Rick Buck Song Koh read Completion of Toa Payoh New Town

- Meira Chand read an excerpt from A Different Sky on the Hock Lee Bus Riots.

- Marc Nair read his poem, Mas Selamat from Postal Code

- Mhd Sharif Udin read his poem, Little India Riot: Velu and a History in Bengali

The book also contains prose excerpts and poems from Alfian Sa’at, Robert Yeo, Said Zahari, Goh Sin Tub, Dave Chua, Christine Chia, Gopal Baratham, Stella Kon, Boey Kim Cheng, Felix Cheong, Toh Hsien Minh, Tania De Rozario and others.

The book is a gateway drug encouraging the consumption of other works of leading Singapore writers.

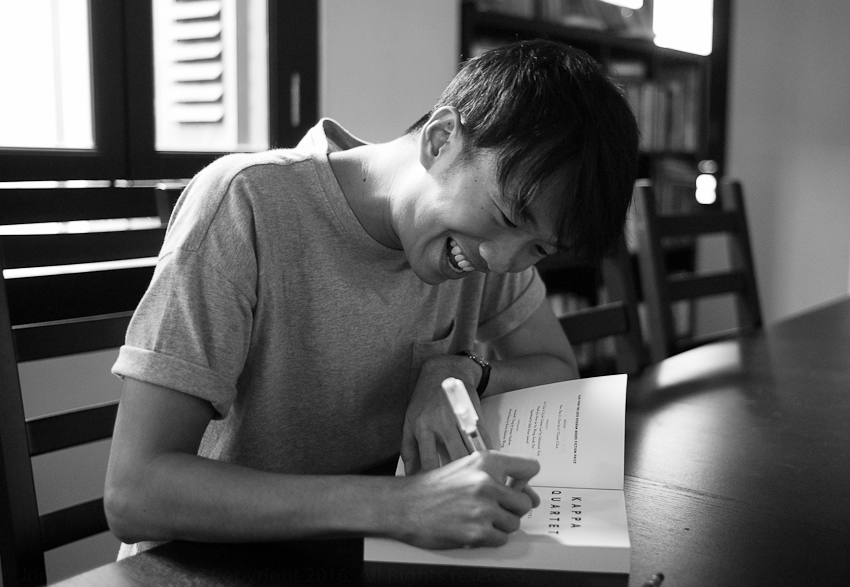

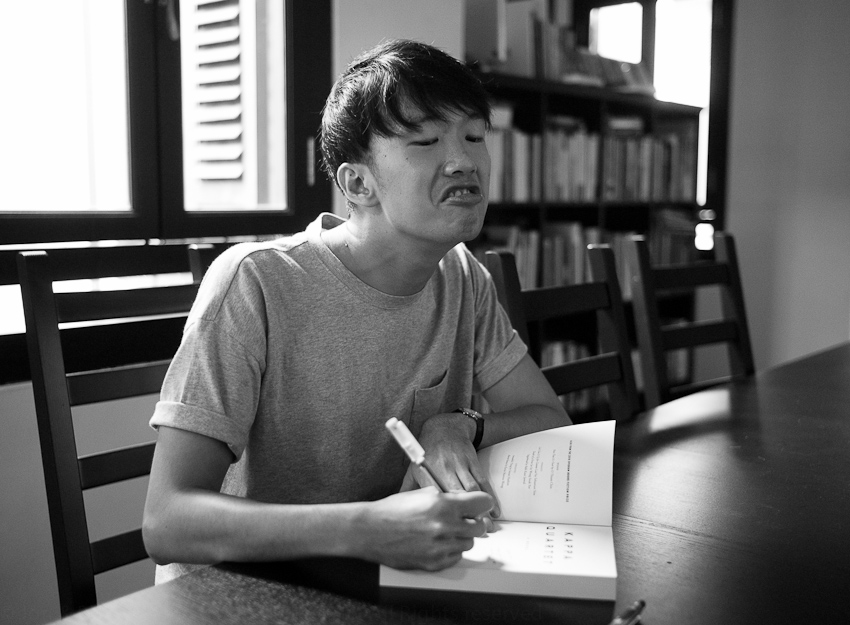

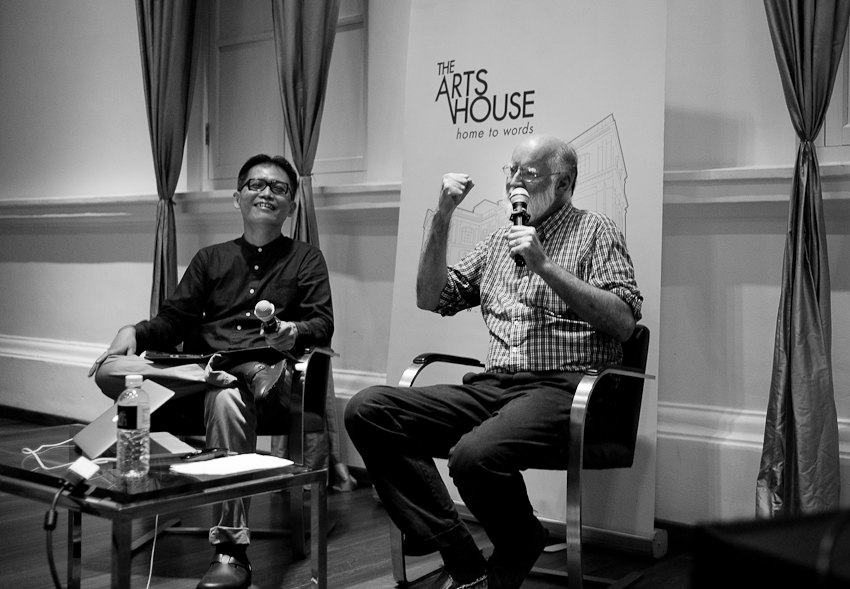

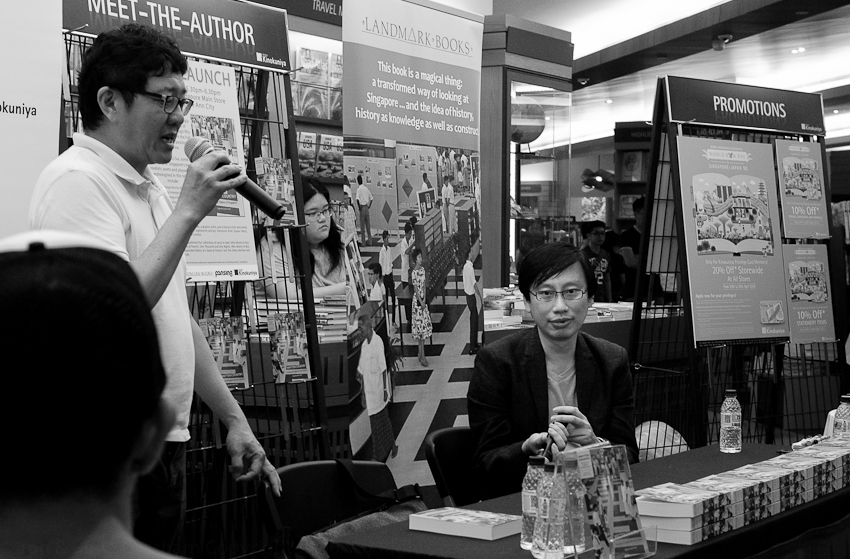

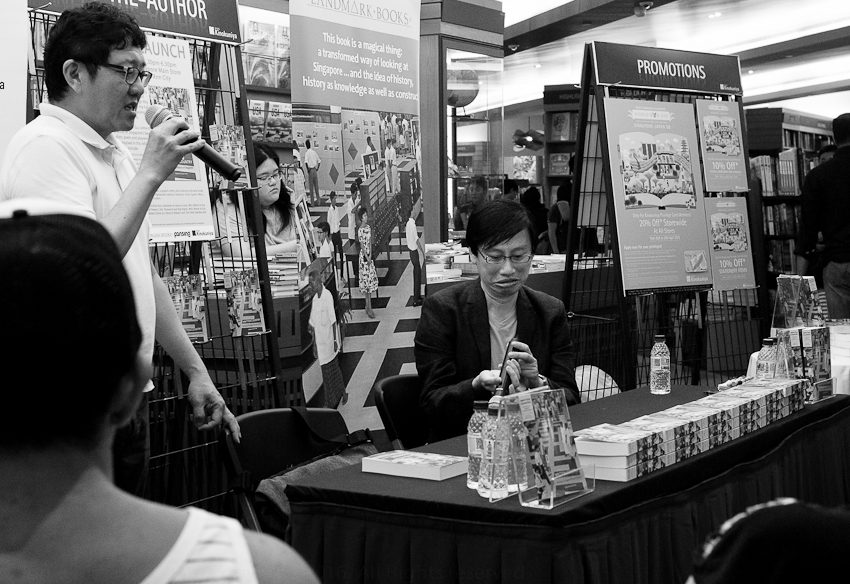

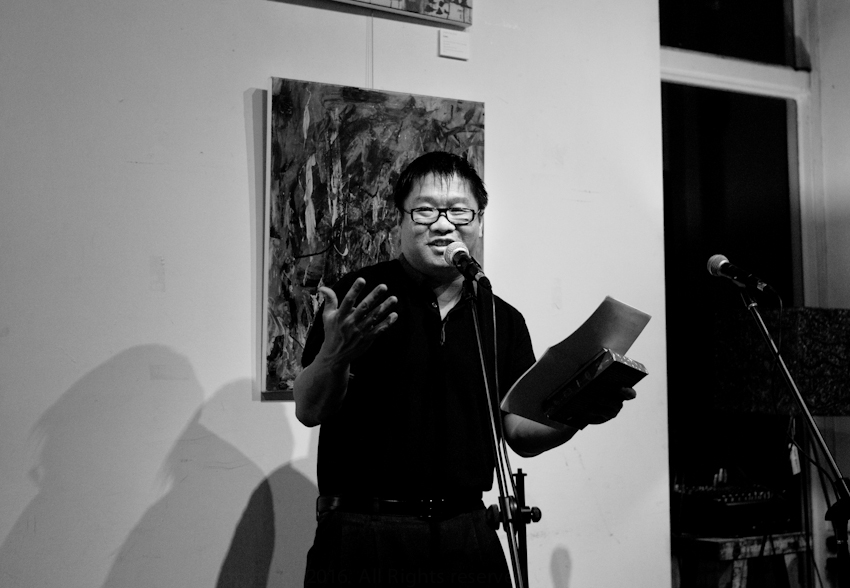

Landmark’s founder, Goh Eck Kheng, did not expect Gwee to do so much work editing the book. Gwee probably did not expect to do so much work either. He ended up looking at a ‘couple of thousand Singaporean English titles’ and whittled that down to 54 pieces. Gwee’s expression after the suggestion of another volume of literature covering pre-war events can be seen above.

My only other question is where was the kachang puteh and potong ice cream?